Djibouti & “Afar Triangle”

a cradle of human evolution

Head of vast continental rift

The Afar Triangle - also known as the Afar Depression - is clearly seen in the figures below as a light grey triangular region at the head of the vast 3000-km East African Rift which enters the Afar Depression at its southwest corner.

The Afar Depression is now the hottest place on earth for year-round temperatures, but was once possibly the very cradle of humanity. It is now a 'hotbed' of earthquake activity, as shown in Figure 2.

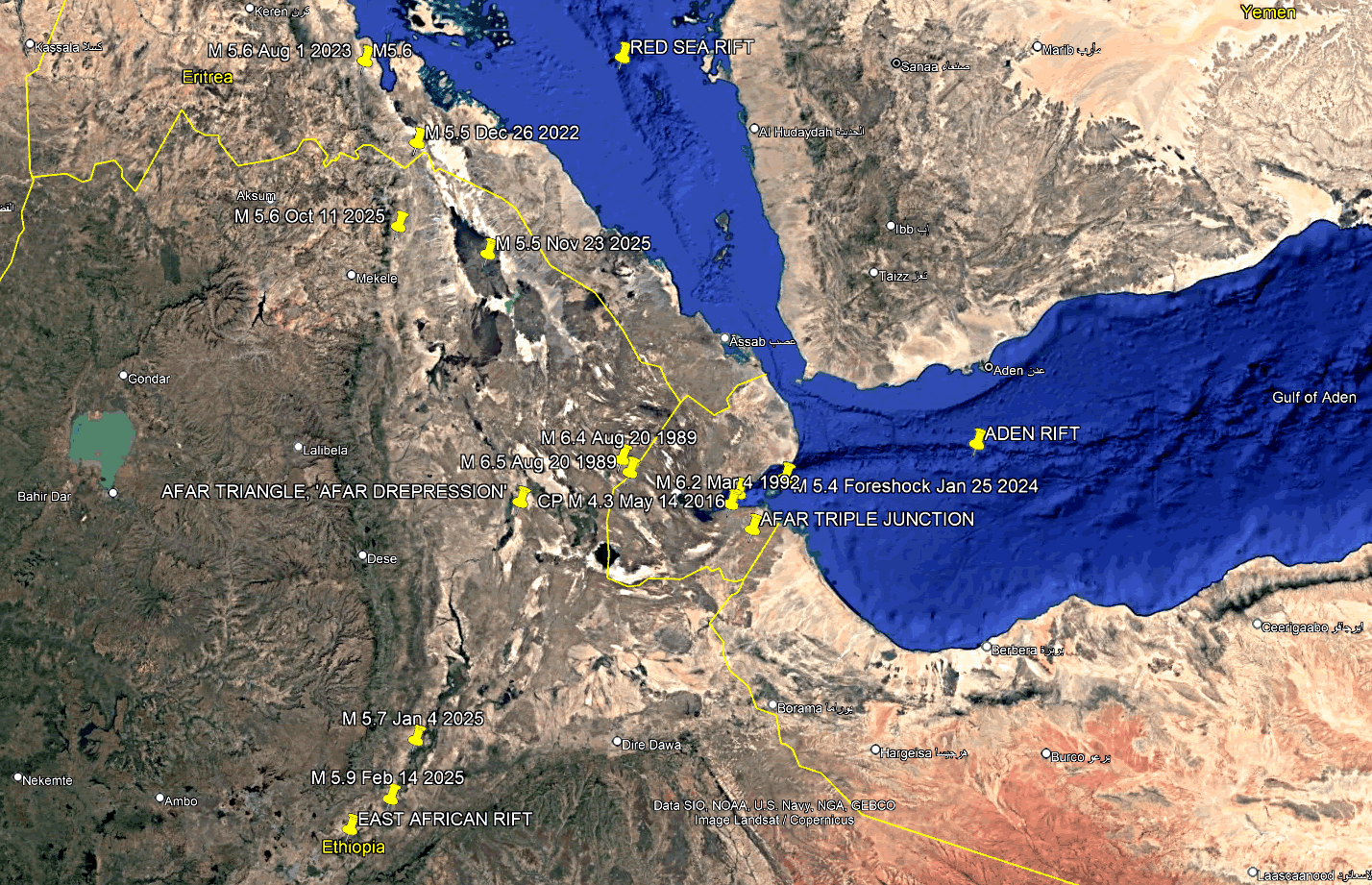

This is because the Afar Depression sits at the junction of three tectonic plates – Arabian, Nubian (African) and Somalian plates – and contains the so-called Afar Triple Junction which is said to be at Lat 11.30, Lon 43.00, only some 35 km SW of Djibouti City: all three M 6.2-6.5 earthquakes of 1989-1992 occurred within 140 km of this Afar Triple Junction (Figures 3-4), and Figure 2 shows a very strong cluster of large events about this point.

The three arms of the Triple Junction - East African, Red Sea and Aden Rifts (Fig. 1) - are said to have a near-perfect separation 120 degrees between each. However, where are the most important earthquakes occurring?

Most of the important earthquakes in this region are confined to the Afar Triangle or Depression: their spatial and temporal occurrence and population dynamics are the subject of this investigation which is devoted to developing practicable early forecasts of large events to save lives and property.

Figure 1.

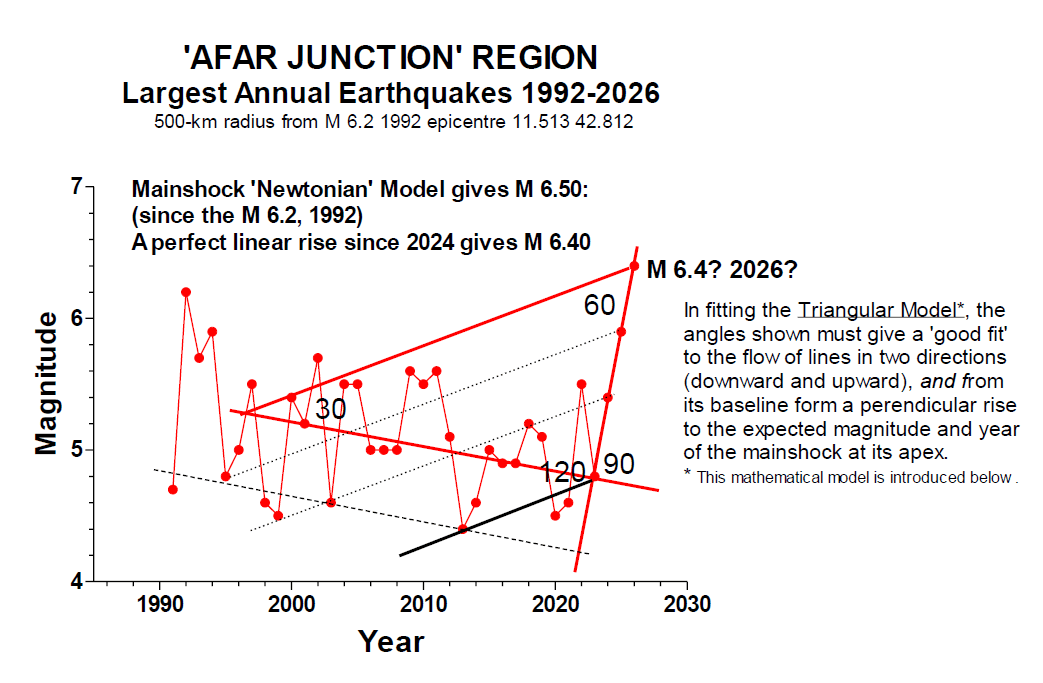

Sequence of Largest Annual Earthquakes in the 'Afar Triangle' and border areas, within the given coordinates. Note that five totally independent modelling approaches yield very similar estimates for the size of the forthcoming mainshock in 2026. The M 4.3 mathematically-critical precursor (PC) of 2016 is shown on the attached Google Earth image as just offshore Djibouti and close to the M 5.4 foreshock of 2024. The general overall decline in the size of annual events between the mainshock of 1989, and the lowest point (the CP M4.3 of 2016) was significant (P<0.018), and the rapid rise following the 27-year decline is obvious, if not somewhat ominous.

Figure 1b.

By comparison with the larger rectangular ‘Afar Triangle’ Region (Figure 1), this graph shows the sequence of Largest Annual Earthquakes in a smaller circular region of 500 km radius from the M 6.2 of 1992, just 38 km west of Djibouti City – a comparison highlighting the robust nature of the Mainshock ‘Newtonian’ Model which yields very similar forecasts for the next mainshock.

In this second graph, the mathematically Critical Precursor (CP) was a M 4.4 in the Red Sea on May 10 2013 about 368 km north of Djibouti City. Whereas the final 90-degree jump point was a M 4.8 only 86 km east of Djibouti City. It is noted that the fitted Triangular Model does not stand alone and if it appears to fit a data set that does not prove that a mainshock will happen at its apex which represents a particular magnitude and time of expected occurrence. However, the corollary is that if it does not fit then the forecast is wrong; this seems to apply to retrospectively tested events and its application is now being evaluated prospectively.

This event is certainly imminent, but when?

(answered via the author’s specialised timing models)

Now expected Mar 15-20, due date Mar 17

(All graphs and comments to be updated as soon as possible)

Page updated March 3, 2026

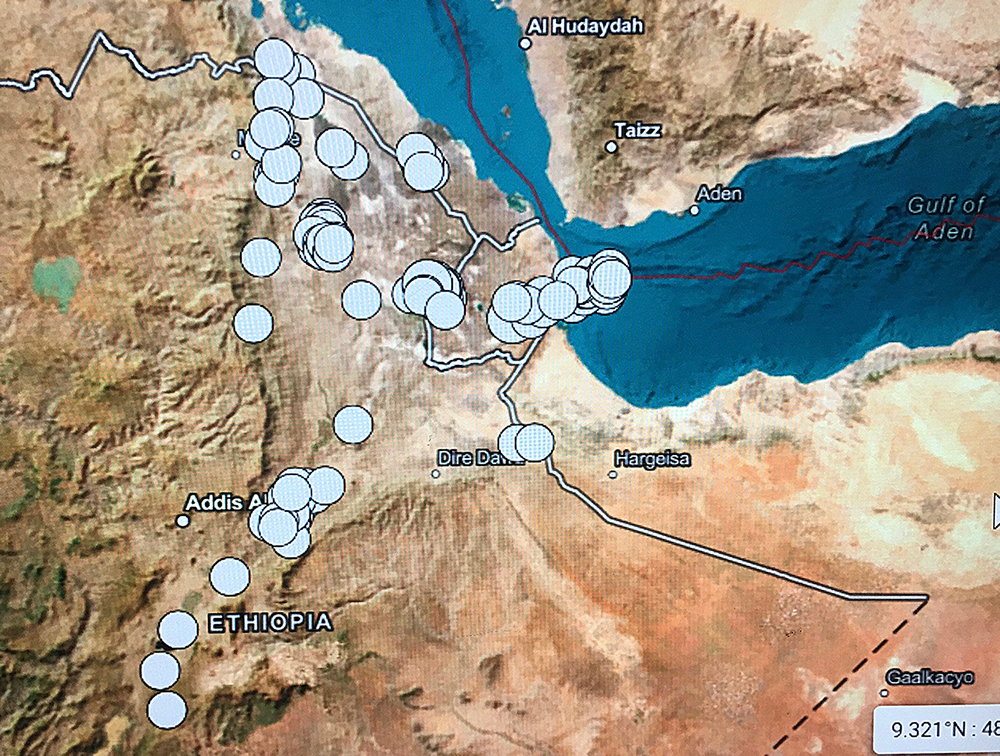

Figure 2.

This USGS Earthquake Search image shows the distribution of 123 M 5.0 and greater events since 1989 in the Afar Triangle region which is also known as the ‘Afar Depression’ by earth scientists. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Afar_Triangle).

Figure 3.

This image of the Djibouti region shows the locations of important earthquakes relative to both the 1989 M 6.5 mainshock and the current expectation for a M 6.5 event on about Feb 2*, 2026. The view shows mathematically-critical precursors (CP) and foreshocks for both periods: these are all offshore close to Djibouti City, in the nearby Gulf of Tajura, whereas all M 6 events are on land within 100 km of the coast. The CP events for both periods are of a very similar magnitude, as are the foreshocks. The next mainshock is also expected to match that of 1989”. [credits to Google Earth Pro and USGS Earthquake Catalogue].

Figure 4

This closer view of Djibouti shows more clearly the relative positions of important precursors and foreshocks preceding the mainshocks, as already outlined for Figure_3.

Figure 5.

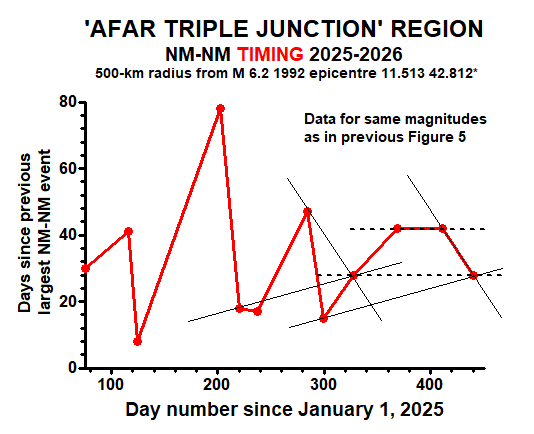

Sequence of largest monthly magnitudes between new moons since Feb 14, 2025, in the Afar Triple Junction region region within a radius of 500 km from the M 6.2 of 1992 near Djibouti City.

It is fascinating that the patterns in a graph like this are a microcosm of yearly patterns, with several of the main features:

(1) A high degree of parallelism between events which the author has found throughout his entire career to be perhaps the most important expression of symmetry within bodies of data; it also confirms here a high level of homogeneity for this body of interacting earthquakes.

(2) Another form of symmetry, or parallelism, is in the timing of major events: most mainshocks are preceded by a major event ‘one year’ prior to the main event (or an expected event) as here we see a M 5.9 on Feb 14, 2025, and an approximate M6.45 mainshock expected about Mar 15-20, according to the analytical timing module represented by Figure 6.

(3) As in Figure 5, any long sequence of largest annual or monthly events will exhibit a decline after the first large event followed by a build-up to the next mainshock. In the mid sequence of low events there may be a period of no recorded events, as here in Figure 5 with no events over M 3.8 recorded for two months.

(4) There is usually a strong drop in events prior to the mainshock: indeed, there may be no further events prior to the final week; in the case of Japan’s M 9.1 this period lasted one month with no events above M 4.0 until the final week.

Figure 6.

This graph shows fluctuations in the time between largest monthly events, for the same lunar periods as in Figure 5. The time between consecutive monthly events is plotted on for each month as the number of days since the previous largest NM-NM event (Y-axis), in relation to the actual day of each month's largest event plotted on the X-axis. In this analytical interactive module, the time between events should oscillate about the lunar period of approximately 29.5 days, as they do here with a mean of 29.6 days. The values prior to all large events, or mainshocks, should resolve towards this mean level - and this graph, via parallelisms confirming symmetry, gives the expected event on Mar 15, at 28 days since the previous M 4.6 event.

Figure 7.

Mainshock Geometry: ‘The 90-degree Jump’

Main shock events are characterised by a sudden large jump of 2-3 magnitudes from the penultimate largest monthly or yearly event: a jump that occurs at about 90 degrees to a baseline or ‘line of fall’ representing the decrease from largest to lowest magnitude in the prior sequence of monthly or yearly events, as in Figure 7 for the preceding 12 months.

This graph provides the simplest and clearest example of the author’s so-called ’90-degree jump’ in the geometry of mainshocks, as more than thirty of the world’s large events have now been re-examined for this intriguing and profoundly important aspect of earthquake dynamics and geometry – further aspects of which will be highlighted on this website.

This graph provides the simplest and clearest example of the author’s so-called ’90-degree jump’ in the geometry of mainshocks, as more than thirty of the world’s large events have now been re-examined for this intriguing and profoundly important aspect of earthquake dynamics and geometry – further aspects of which will be highlighted on this website.

Much might be inferred from Figure 7 which gives graphical evidence of what must be happening seismologically. For example, note the substantial period over seven months without an event recorded when the rocks within fault lines must have been fully locked up. This event was again followed by a marked downturn in largest events over the next three months until the magnitude 3.9 of July 22 became the jump-off point for an unexpected large release of energy 29 days later with the M 6.5 mainshock on August 20, 1989.

The ’90-degree jump’ provides yet another forecasting model, and also a check on other models which must all agree on the magnitude and timing of a forecast. Blinded by the 90-degree’s seemingly unpredictable jump, it was not until Sept 4 last year (2025) that I recognised its apparent geometric consistency and answers which also aligned with the forecasts of other models for the magnitude and timing of a forthcoming mainshock.

But the predictive power of this modelling does not rest on any one event or pattern, nor on any one location: rather, all patterns, all analyses, all models, work in concert.

This website is committed to sharing the intriguing and revealing patterns of earthquake dynamics and behaviour gleaned from just three parameters - the magnitude, timing, and location of earthquakes that any student can easily access.

Most of these patterns – including a new geometry which is gradually unfolding on this website – have never been seen before or, at least, never been examined as the mathematical basis of a body of research which has an ecological perspective. There is sheer mathematical beauty to these repeated patterns and synchronies which together have an amazing level of predictive power.

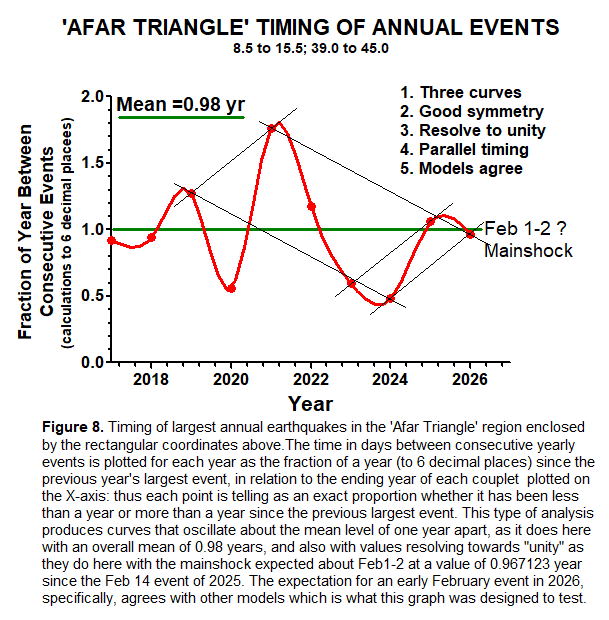

Figure 8.

Use of Timing Patterns

(1) The flow of time between largest events prior to a mainshock is ideally described by three relatively smooth curves, the mid curve being the largest. Failure to get this result usually means that the chosen search zone contains major statistical ‘outliers’ and thus the data are not ‘homogeneous’ and lack symmetries, in which case a smaller study zone should be used.

Please also note that so-called ‘three-curve patterns’ repeat throughout the year, and therefore any resolution which ends with consecutively large earthquakes about one year apart do not necessarily indicate that the last event will be a mainshock: rather, this will only be true if all other models agree on the timing.

(2) Classical sets of three curves display parallel trends and ‘connectedness’ of points which allows quantification of timing. The three curves should span at least ten months for monthly models and at least ten years for annual models, as in Figure 8: that is, enough to describe three full curves.

(3) The flow of time between events resolves to “unity” (that is, largest events settling close to one year apart in annual models, or one lunar month apart in monthly models). Thus, from other modules we expect the next mainshock Mar 15-20, just over a year since the M 5.9 of Feb 14, 2025.

'The Calm Before the Storm’

Lately there are very few earthquakes in the Afar Triangle region and Triple Junction in the Horn of Africa. And yet this research website is expecting the possibility of a M 6.4-6.5 during Mar 15-20, 2026, in just a few days’ time. Are previous events supportive of the possibility for this event now?

Compare events for 1989’s M 6.5 with today

Same or similar mainshocks: currently expected M 6.4-6.5.

29-day ‘calm’ without other events: Feb 2*, 2026, will be 29 days.

Resolution to 29.5-day lunar period between final events.

Same M 4.5 ‘90-Deg Jump Points’ in both penultimate years.

Penultimate year strong magnitude drop from prior year(s).

Mainshock at Full Moon + 3 days or expected timing, Feb 2*.

But beware: these intriguing similarities do not prove any thing about size or timing of an event.

The recent M 4.3 of Jan 21 has 'moved the goal posts': important

new modelling now revises our expected mainshock to a estimated

M 6.4 about *Mar 15-20, due date Mar 17

Supportive information will be added as soon as possible,

and this page and its graphs are currently being updated.

Latest update March 3, 2026

Figure 10 (revision of Fig 6)

Figure 11 (review of Fig 8)

Sources: The Afar Triangle - www.researchgate.net, www.volcanocafe.org, Afar Triangle - Wikipedia and USGS Earthquake Catalogue, Google Earth Pro.

**Data were analysed with a spline curve generated using GraphPad Prism version 5.01 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA, https://www.graphpad.com